Founder & Director; Instructor, Renaissance Drawing & Painting, Oil Study, Child & Teen Classes

JAMES ROBINSON earned his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from Columbia College, Chicago in 1981. He spent six months studying Italian Renaissance and Baroque Art through Loyola University's Rome Center in Rome, Italy. During that stay he traveled extensively throughout Europe, visiting museums to gain a firsthand understanding of art history. On his return home Jim entered the field of children's text and trade books where he worked in production, design, and illustration for nine years.

Wishing to expand his knowledge of drawing and painting techniques further Jim moved to Minnesota to study at Atelier LeSueur and Atelier Lack, schools which emphasized the disciplines of nineteenth century academic and impressionist painting. Following his graduation, Jim became an instructor in the full time program at The Atelier, teaching drawing, painting and composition to adults pursuing careers in the fine arts. He has also taught workshops on color theory and Renaissance oil painting techniques throughout Minnesota. In 2004 Jim was nominated to be listed in Who's Who Among America's Teachers, a publication reserved for the top 5% of teachers in the United States.

In addition to teaching, Jim has also written and lectured on artists and the importance of art history in professional artists' lives. His articles have been featured in international publications.

In 1993 Jim founded The Art Academy:

"I knew at a very young age that I wanted to be an artist, but I grew up in the 1960's. The sixties was a vibrant decade in many ways; but it was an abysmal time in art education if you wanted to learn how to draw and paint following traditional methods. Consequently, every place my parents took me, from the local art school to the Art Institute of Chicago's children's program, shared a similarly modern teaching philosophy. We were given a lot of supplies, asked to express ourselves, and then we were told how wonderfully creative we were regardless of what we produced. The absolute minimum amount of instruction took place because it was believed anything more would squelch our artistic uniqueness.

"This proclivity continued through my college years. I received my BFA without ever being taught the proper way to hold a brush, how to apply color theory to a specific pictorial problem, or how to draw something accurately and correctly without encountering a struggle. Art history was an afterthought and its link to art training was completely ignored. As students, however, we were thirsty for knowledge and understanding. We tried to teach ourselves everything we could from previous generations of artists. As I began reading the works of Kenneth Clark, Bernard Berenson, Howard Hibbard and others it began to dawn on me: An artist of the past received more training in a few months than I had in all my years in school. The technical problems that my colleagues and I faced in our own work were a struggle because we had never been taught how to solve them. Everything was based on the 'teach yourself' principle, which is a very difficult and time consuming way for anyone to learn. As a result, many students abandoned their dreams; very few of us continued on in art.

"The truth is none of us were taught how to see. Andrew Wyeth (1917- 2010) speaks of the importance of this: 'Art, to me, is seeing. I think you have got to use your eyes as well as your emotions, as one without the other just doesn't work.' Of course, the seeing of an artist is different from the seeing of the average person. It's based upon a thoughtful understanding of art history, advanced technical training, direct observation, and a lot of hours spent in front of an easel working with a knowledgeable instructor who can explain the intricacies of art and nature in the simplest terms. Simplicity, in fact, is always the key. The great artists who have helped shape our culture did not produce huge volumes of work by painting in a complex manner. They reached their goals and achieved their recognition through simplicity and understanding. 'It is not enough to believe what you see, you must also understand what you see,' wrote Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519). It is why I've searched out so much post-graduate training, to acquire that knowledge and skill.

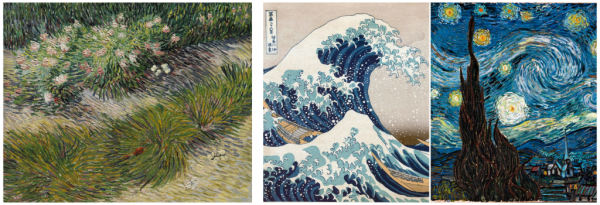

"Though my personal tastes center around Rembrandt, Vermeer and the other great artists of the seventeenth century, then culminate with an interest in the great representational movements of the 1800's, I can also appreciate abstraction in its most dignified and decorative forms. What has been eliminated from the equation when considering the majority of these painters, however, including the lives of notable abstract painters, is their past. Take Georgia O'Keeffe as a case in point. Here's a modern painter who has widened and enriched our world, but that didn't just happen. Look at her training: drawing lessons at age eleven, painting lessons at age twelve where she copied other artist's works, off to the Art Institute of Chicago to study anatomy with John Vanderpoel, off to The Art Students League in New York to study painting with William Merritt Chase and F. Luis Mora, and then composition with Arthur Wesley Dow and painting with John Marin at Columbia University. Then there's the influence of Alfred Stieglitz and the expanse of the great southwest. It was these cumulative experiences, combined with her inborn talent, that helped formulate her work. One was not independent of the other. This is something you find repeatedly throughout art history – a solid foundation in the fundamentals during one's formative years was a preparation for mature achievement.

"While in the past a structured and focused training was desired and revered, today in many art schools it is summarily dismissed. Students are encouraged to leap from activity to activity and medium to medium without ever being asked to put in the time or effort to master any one of them. Usually, this is done in the name of creativity. The end result, though, is often a lessening of skills and a lowering of standards. Freedom is less a key to talent than commitment.

"The artists of the past were very conscious of this fact and were very centered on what they were doing. Even thematically they were very focused. Monet, for example, was a painter of landscapes. His portraits and still-life were occasional. Consistency and dedication were a prerequisite to achievement. Everyone acknowledged that.

"In the last hundred years, however, we've fallen in love with the romantic notion of 'genius' – the untaught artist coming from nowhere and revolutionizing the world. The truth is this has rarely occurred in the history of art. When you read Van Gogh's letters and find him writing: 'I work as diligently on my canvases as the laborers do in their fields.' such notions quickly fade away and a more realistic view of an artist's life emerges.

"I founded The Art Academy because I believe skill development and creativity are closely linked. I want to give children and adults the opportunity to really learn how to draw and paint well so they realize they're much more talented than they ever could imagine. I want them to see that the link between effort and achievement in art is very similar to other activities they're involved in, and it's not just something miraculously bestowed on a very few by some 'higher power'. I want them, too, to have the opportunity to get a solid training in fundamentals. I firmly believe that a rich understanding of drawing, painting, color, and composition is the foundation for success in all the varied forms of expression in art today. We continue to stress the basics in music and dance education and I believe it's still applicable in the visual arts.

"I worry, too, about the way people are moving around today, sampling one thing now and another thing later. In an article published in the January 27, 2002, New York Times entitled Practice Makes Perfect; writer James Schembari described this phenomenon regarding his children: My three sons, ages 7 to 11, play on community baseball and T-ball teams and once played organized soccer and basketball. They have taken trumpet lessons and chess classes. My daughter, Marian, 14, has been a member of the Brownies, has played the violin and is now taking piano lessons. She has also joined the drama department and the choir at her school….Kristin A. Moore, the president of Child Trends (a nonpartisan research group in Washington), said there was a downside to all this. '(It's) good for children until you get past the midpoint and everyone is overwhelmed by the sheer quantity.'

"Instead of quantity, I want to present children and adults with an art environment where quality is the message. It seems logical to me to create a program based on the values of consistency, dedication and long term goal-setting when one of the most important things we want to achieve in life and pass on to our kids is a sense of commitment and self-worth. You just don't get a full sense of achievement when you're dabbling in things. Mastery and its related feeling of fulfillment are a much more enriching life-force for a person to grasp than repeated variety.

"Quality is most often achieved by focusing on one activity over an extended period of time. We see this with Olympic athletes who attain proficiency by devoting themselves to the mastery of one sport. Well, it's the same with art. Consistency is the key. By bringing this philosophy and a tradition of reverence for the technical methods of the past to our teaching an amazing thing happens: An ever-expanding sense of pride fills our students for having the courage, strength and understanding to work through a drawing or painting to its ultimate conclusion. It's an important life skill that filters into every aspect of a person's life.

"So much has been misunderstood in art education over the last century. Today the scales have been tipped to emphasize creativity and individuality to the exclusion of skill development. The belief is constantly put forth that artists are always creating, always inventing something new, and therefore an arts program should always be creative. But history doesn't bear that out. In fact, very few artists have spent their careers continually inventing new forms of expression. Rodin (1840-1917) declared: 'I invent nothing; I rediscover,' and Degas (1834-1917) exclaimed: 'Art does not expand, it repeats itself.' What art careers are really about is exploring a theme over and over to the point of revelation. Yet, since Picasso and other 20th century abstract artists, we've come to believe that newness is the key to artistic fulfillment.

"Throughout history there have always been discussions on the most effective way to teach students art. Interestingly, there has been a considerable consensus among noted artists as to what that training should emphasize. 'Teach only uncontested truths, or at least those that rest upon the finest examples accepted for centuries. You can be sure that once out of school the pupils will create the truth of their own time from this noble tradition,' wrote Hippolyte Flandrin in 1863. It was this philosophy which made Flandrin one of the most highly regarded painters and teachers of his time. Today, you have artists like Frank Stella declaring: 'One learns about painting by looking at and imitating other painters,' and Audrey Flack lecturing: 'Art students often worry about losing their originality to instructors, other artists, or even themselves, through their desire to copy work they admire. There is nothing anyone can do to take your originality away from you!' What is repeatedly stressed by a vast array of artists across many centuries is that a good amount of time of one's early training should be spent on fundamentals.

"When it comes to our younger students, my personal desire to teach them comes from a growing concern about children and teens who have a calling to choose art as a career. Too often they will go off to attend an arts college where they will acquire a large debt and graduate without any marketable skills. Students graduating from these organizations often face a future that can be less than bright – working off a student loan in a low paying, dead-end job while they wait for their 'big break'. For these career-minded individuals The Art Academy has something special to offer. At a young age our students are shown that if they work hard they can become personally responsible for their own success. As they finish more projects and their skills improve their portfolios become more impressive. With the work they've done in class and the projects they complete on their own they have the resources to compete for scholarship money to offset student loans. Most importantly, though, they get a head start. Our students approach their future with an understanding of drawing and a wealth of experience in watercolor and oil painting. This background, combined with what they will learn in a post-secondary school, makes it possible for them to achieve success at an early age. These kids sense a hopeful future as they enter adult life.

"The school is a labor of love. For a handful of hours each week a group of dedicated individuals come together to pass on traditional drawing and painting practices to children, teens and adults. I've spent years reading through texts, studying old studio practices, trying to decipher some of the methods that were used to teach apprentices and young artists from the fourteenth through twentieth centuries. From that knowledge we've organized a simple arts program that passes on a solid foundation to our students. We review its effectiveness on a regular basis to continually improve its efficiency. I started teaching out of my home and from there things grew. Now we have students coming from as far away as Wisconsin to attend our classes.

"There's something infectious about teaching art, to see students produce work they never dreamed they were capable of doing. It's very satisfying to know you're affecting a life in a positive way. And it's not just one life. When students take home works of art that they create they have something tangible to share with the world. That's one of the great things about the methods we pass on to them. Unlike music or dance, there is nothing ephemeral about a drawing or painting properly done. In a material sense it is a permanent record of a specific time and achievement that lasts. While it's gratifying to know that our students will be showing off their work to others today, the real thrill is contemplating that the painting some student has just completed will be around to grace and inspire future generations tomorrow. Think of the continuity. There's real power in that."

You must be logged in to post a comment.